“We started the season with debts for two years. This year, we are at the end of our lending capacity,” says Anne Roussel, co-owner of the firm Cadet Roussel in Mont-Saint-Grégoire, Montregi.

Consumers must take out their membership to receive organic vegetable baskets during the summer. Cadet Roussel's farm produces 500 baskets a week during normal hours, year-round.

Subscriptions allow producers to start the season with money in their pocket, but this is not the case for the pioneers of the organic basket. The end

of the pandemic.

If the difficulties faced by Cadet Roussel are anything to go by, it was one of the first farms to adopt the organic basket model.

It's a real warning cry and I'm not the first to say it. There are many farmers in the last stage.

Difficult weather conditions have prevailed for the past two years. The number of farms is decreasing. Farmers get outside employment. Moreover, Financière Agricole advised us to do this: find a job outside to continue our farm.

she said.

To keep its head above water, this year, the farm is trying a new model, where customers become partners in a community farm. This is the model available in the United States and Germany.

At least 250 partners have initiated the project so far, representing 70% of the financial target. This requires, the company writes, $625,000 to supply vegetables to approximately 300 households annually

.

The problem is that today is due on Friday. A decision on whether to start the season will be made this weekend, the co-owner promises.

Anne Roussel, co-owner of Cadet Roussel Farm

Photo: Radio-Canada

Inflation, climate and competition

Other farms, such as Mon Basket Bio in Saint-Felix-de-Valois, have also noted the decline in popularity of vegetable baskets. During the pandemic, his small farm yielded 150 baskets, tripling its normal output. In the past 2 years, the number has dropped to 50 baskets, says owner Ann Beaudry.

To run his farm, he works alone 70 hours a week without paying himself a salary. His daughter is preparing to come to work with him, but he does not know if he will be able to increase his income.

According to him, offering organic baskets during the pandemic left many customers disappointed. Because of the sudden supply, many producers jumped in without experience. However, he sent this message: Try other producers. If you want to choose your basket, it is possible! Above all, don't give up just yet!

The general director of the Network of Family Farmers, Emilie Vieau-Drouin, for her part, cited the economic slowdown, changes in the climate, labor shortages and competition to explain some farms' struggles.

New players added. Big grocery chains here can find everything you can imagine in one basket and they do home deliveries. There are also other types of businesses that have emerged on the landscape

She explains.

When companies come to offer a product like this, it is sure to create unfair competition in the sense that it is great. As these types of deliveries take place across the country this can be detrimental to certain farms.

We understand that today's life is so crazy, the pace is so fast not only to cook, but also to go to the grocery store or pick up your basket, but we want to remember that our product is unique. It's about meeting the people who produce our food. To stop for a moment and meet them, we think it's magic

Adds a general director.

Luffa Farms criticized

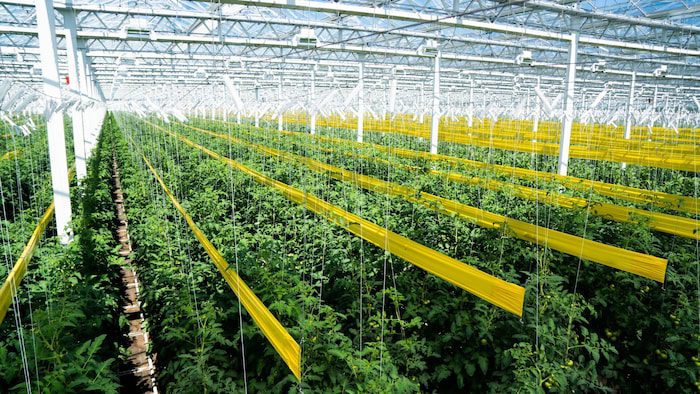

Luffa greenhouses produce vegetables throughout the year.

Photo: Radio-Canada / Alexis Boulianne

Émilie Viau-Drouin did not want to name specific companies, but Fermes Lufa is one of these new players, who are expanding and disturbing.

In the show anything can happen, The former mayor of Huntingdon, Stefan Gendron, who lives on a farm, criticized Luffa. To industrialize agriculture on the rooftops of Montreal

Damage to smaller municipalities.

Anne Roussel was also amazing to watch Vegetables reach rural areas from Montreal

. How can the people of this region not say to themselves: ''Where is my nearest farmer? I encourage him! I wish there was farmland!

Lufa Farms produces vegetables using greenhouses built on Montreal rooftops, but offers customers whole products through their online platform. Fewer than 32,000 families are buying loofah baskets, says president and CEO, Mohamed Haze, who denies competing unfairly with local producers.

Our main competitors are banners, products from outside of Quebec, not local producers. In contrast, loofah products represent only 10%, while the remaining 90% are products from other producers, including around a hundred organic farms.

The Lufa platform allows producers to sell local produce directly to households without developing a distribution network.

He explains.

Also, times are tough for Luffa Farms. For two years, sales have slowed and the company has been facing financial losses, which Mohamed Hage hopes will reverse in 2024.

In 2020, the company signed on to build a new rooftop greenhouse, a new warehouse and an indoor farm. She managed her projects despite the reduced income, but she found no one else.

Hear a report from Karin Mate In the show It concerns us At the ICI premiere.

More Stories

Sportswear: Lolle acquires Louis Garneau Sports

REM is still innovative enough to foot the bill

A trip to the restaurant with no regrets for these customers