(Quebec) Is Quebec, a totalitarian state? Nowadays, only a conspirator can speak such words. But under the sharp pen of the Chief Justice of the Superior Court, such an affirmation evokes surprise.

Posted at 8:00 am

It’s been 40 years this week. On September 8, 1982, Judge Jules Deschenes declared unconstitutional the provisions of Bill 101, which reserved entry into the English-language school system in Quebec for children of parents educated in that language. Quit the “Quebec Clause”: Children whose parents completed part of their studies in English “in Canada” are eligible for English-language elementary and secondary schools.

“The invalidation of the Quebec clause was seen as an attack on a fundamental, very delicate, language of instruction,” observes Jacques Beauchemin, a sociologist specializing in language issues. “The population realized at the time that it was not good news,” Mr. Beauchemin recalled. Two years later, the Supreme Court upheld the Deschenes ruling.

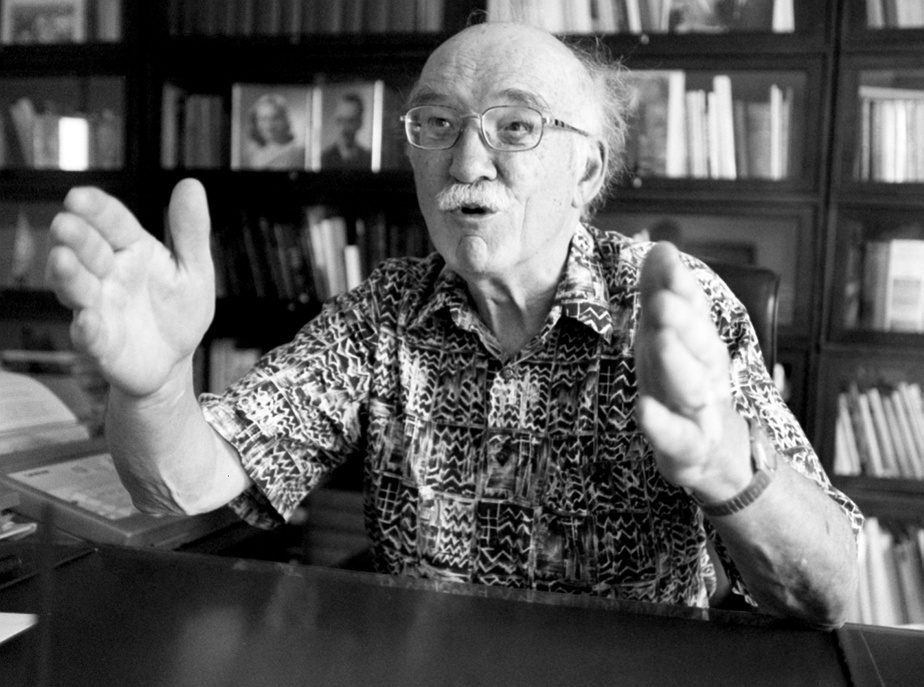

Photo by Robert Skinner, Law Press Archives

Judge Jules Deschenes, in 1999

By December 1979, the Supreme Court’s Blaikie ruling had already invalidated the articles of Act 101, but it concerned the courts’ language, interpretation of statutes, and more theoretical questions. Less obvious issues are the language of instruction, which has been at the center of language controversies in Montreal for decades.

Judge Deschenes’s ruling sparked surprise, not so much for its tendency toward the incendiary tone adopted by the magistrate. This formulation sheds harsh light on the evolution of sensitivities and public debates over four decades. Quebec argued that the “limitation” imposed was not a “prohibition” of the right provided for in section 23 of the Canadian Charter, which had just been ratified. Above all, advocates for the Levesque government insisted that collective rights should be prioritized over individual rights.

The answer was stark: “Quebec’s argument reflects an authoritarian conception of society that the court cannot accept. The human being is the greatest value we know and nothing should conspire to diminish the dignity of it. Other societies place the community above the individual. They use the steamroller of the kolkhoz and see only merit in the collective outcome,” wrote Judge Deschenes.

In Canada, every person in Quebec should enjoy their rights to the full […] It cannot be considered an accidental waste of a mass operation.

Excerpt from the judgment of Judge Jules Deschenes

“I am surprised and disappointed by the tone, which is unacceptable from a judge,” Guy Rocher, one of the architects of Law 101, began this week. A few years later, Mr. Rocher went to dinner with the now-retired judge. A former colleague from the University of Montreal. “I told him: ‘You know me, you wouldn’t believe I worked for a totalitarian group!’ Deschenes recognized that he had probably gone too far,” Mr Rocher recalled.

“A Sovereign Law”

Camille Laurin probably hoped these provisions would be declared unconstitutional. But he is determined to “make a sovereign law, not a provincial law”, said Robert Fillion, the father of Bill 101, a long-time collaborator. Despite the reluctance of some members, the Council of Ministers followed him. , Rodrigue Tremblay and especially Claude Morin, then in charge of international relations.

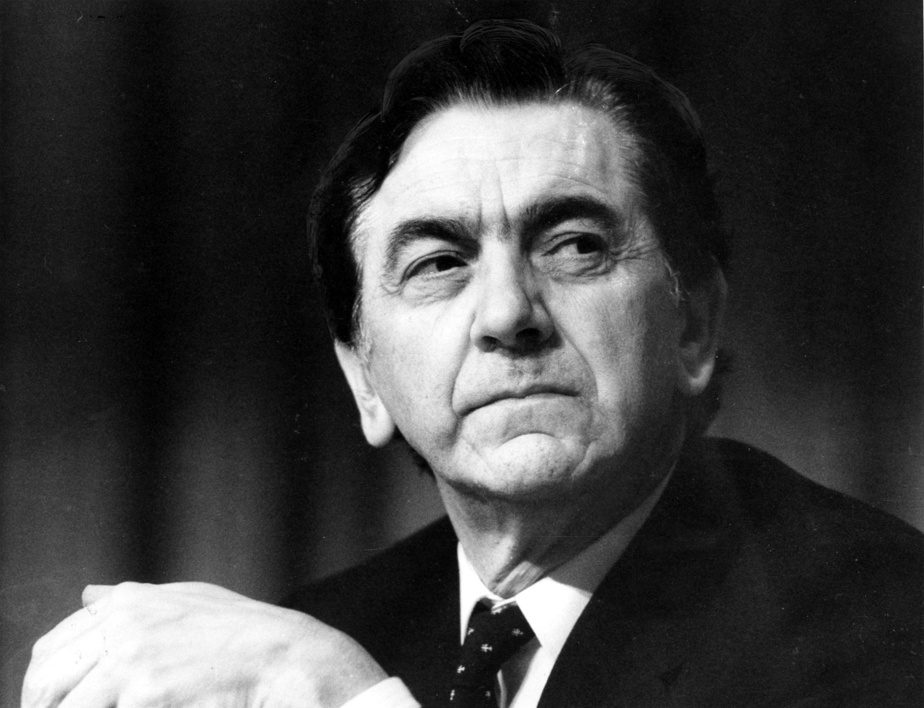

Photo by Armand Trottier, Law Press Archives

Camille Laurin, former Parti Québécois minister in 1983

The debate on the “Quebec Clause” versus the “Canada Clause” continued in the Council of Ministers for a month. Levesque “thought there was a big bone there, but Laurin was able to get people’s attention,” Mr. Fillion recalled. “Like some people, I find that some provisions are almost provocative and it would be better to remove them immediately, because it would harm the whole law,” said Claude Morin. “Jean-Roche Bovine [bras droit de René Lévesque] We were invited to express ourselves, and we did so with the tacit consent of Levesque, who, as mediator, could not take much of a stand”, continues Morin.

As Judge Jules Deschenes delivers his verdict, Lauryn steps up. “This was the first manifestation of the constitutional revolt committed by Ottawa,” explained the late Jean-Claude Picard in his biography of the minister. The Canadian Constitution was adopted in April 1982, and a few weeks later, Quebec lawyers argued over the text of Article 23 on the education of linguistic minorities, which had not yet been tested by the courts.

“It was the first Charter case argued by Quebec,” recalled Jean K. Samson, who led Quebec’s lawyers at the time. “Basically, how can you defend a law that’s not in line with the Charter!”, he began this week. Quebec decided to argue the “reasonableness” of the clause, looking at European law, invoking collective rights.

Mr. Samson was not surprised by the verdict or the tone adopted by Magistrate Deschenes.

We pleaded for a few days. As soon as he spoke about collective rights, he exploded. He accused us of imitating the USSR. His decision was predictable.

Jean K. Samson, about Judge Jules Deschenes

Act 96

At that time, M.e Julius Gray was a lawyer for those who opposed Bill 101. “Today, Bill 96 does not affect the issue of schools,” said Mr.e Gray, in his opinion, was a sign that the legislator was well advised. “The Quebec clause created barriers to movement between provinces,” the jurists said. “The courts have made it possible to improve the law and I am proud to have contributed to that,” he sums up.

Four decades have passed. Doctor of Constitutional Law, Frédéric Bérard did his thesis on linguistic issues. In the debate on secularism, he was a strong advocate for individual rights. But, according to him, it is different when the protection of the language is at stake. “I’m not a big fan of collective rights, but we mustn’t forget that Quebec is essentially a linguistic minority in an English-speaking ocean. It can adopt ways to ensure its survival,” explained Mr. Bérard.

The Quebec clause? Canada provision? “We have to keep calm, we are talking about 80 students a year who can enroll in the English-speaking department in Quebec. That’s two high school classes! “, Mr. Bérard explains.