Image copyright

CBS

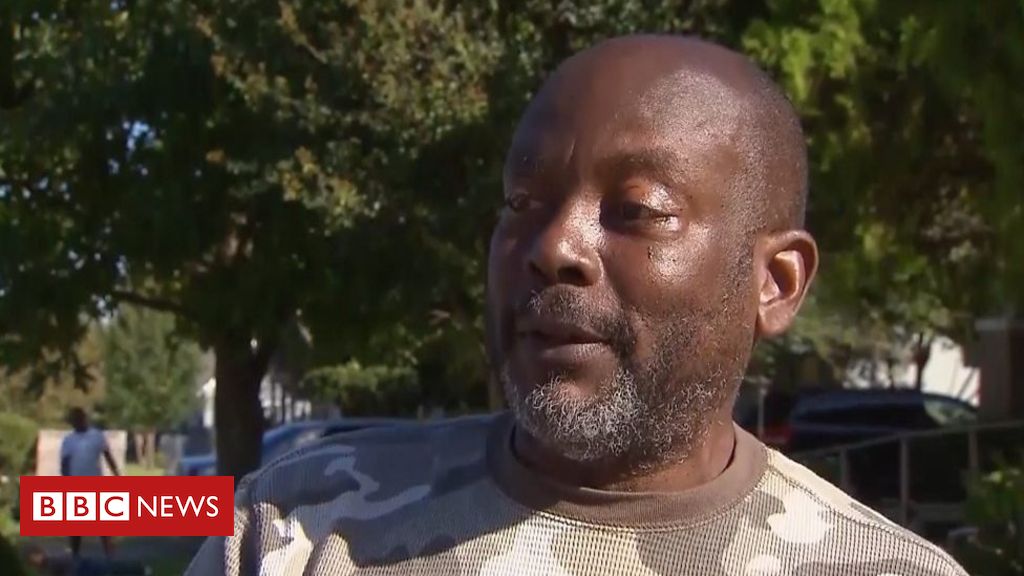

James Smith has never wanted much to do with the police but he called them to check on his neighbour in the Texas city of Fort Worth, because it was late at night and her front door was wide open. Soon afterwards he heard a gunshot, and later saw the dead body of a 28-year-old woman, his neighbour’s daughter, carried out on a stretcher.

James Smith is angry, hurt and tired. Every death of a black person at the hands of a police officer takes him back to the moment in October when Atatiana Jefferson was killed.

“I have to live with this guilt, with this cloud hanging over me for the rest of my years,” he says. Because he was the reason that the police were there that night.

At around 02:30 on 12 October he was woken by his niece and nephew, who told him the front door of their neighbour’s house was wide open and the lights were on.

The owner of the house, Yolanda Carr, had a heart condition and had recently been in and out of intensive care, so Smith was worried something had happened to her.

He went across the road and noticed the lawnmower and other gardening equipment were still plugged in, which he thought was strange.

So he dialled a number in the phone book to request a “wellness check” – expecting that a police officer would come out, knock on the door and check the family was OK.

He didn’t know that Carr was in hospital that night and that her daughter and grandson were up late playing video games.

Image copyright

Amber Carr

Atatiana was saving up to study medicine

He was standing directly opposite the house when the police arrived.

One of the officers, Aaron Dean, had his gun drawn as he approached the front door and then walked around the side of the house to the back garden. Seconds later there was a gunshot.

“When that bullet went off I heard her spirit say, ‘Don’t let them get away with it,'” Smith says.

“And that’s pretty much why I stayed out there all night long until they brought her out.”

Police soon filled the street, but they wouldn’t tell him what had happened. It wasn’t until they wheeled a body out six hours later that he knew Yolanda Carr’s daughter, Atatiana Jefferson, had been killed.

The two families were still getting to know each other. Yolanda Carr had bought the house four years earlier and was fiercely proud of it.

Her house is separated from James Smith’s by a road and their wide, green, manicured lawns.

Image copyright

James Smith

James Smith is reminded of Atatiana whenever he looks across the road

Smith is a veteran of the neighbourhood. He’s raised children and grandchildren there, and five members of his family still live on the same street.

Keeping the yard straight is like a ritual in the area, he says, one that Atatiana’s family had been quick to adopt. He describes Yolanda Carr as a hard-working lady. “She had some problems in life that she overcame and her home was her trophy.”

Atatiana had been staying in the house while her mother was unwell. She was saving for medical school while caring for her mother and her eight-year-old nephew.

A few days before the killing there had been a car crash on the street, James Smith remembers. Atatiana rushed out to help, and she stayed with the people in the car until the ambulance came. That was just her nature, he says.

“She intended to become a doctor,” he says, before going silent for a moment. “But that’s not going to happen now.”

Sometimes he would mow their lawn for them, Atatiana would bring him water and they’d chat. The day that she died she had been mowing the lawn herself, showing her nephew how to do it.

On the footage from the officer’s body cam, released after she was killed, officer Aaron Dean can be seen walking up to a window at the back of the house, where Atatiana briefly appears.

“Put your hands up, show me your hands!” he shouts. He has barely finished speaking when he fires through the window. He never declared he was a police officer.

Aaron Dean resigned before he could be fired. He was quickly arrested and in December he was indicted for murder, but the trial has been delayed by the coronavirus pandemic.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Fort Worth police chief Ed Kraus said he “could not make sense” of why Atatiana Jefferson had to lose her life. In a press conference he seemed emotional as he spoke about the damage that her death had done to relations between the police and the community.

But James Smith doesn’t find any of this reassuring. Atatiana’s death has destroyed what little faith he had in law enforcement.

“We don’t have a relationship with the police because we don’t trust the police,” he says. “So if we can stay out of their way, we’re fine.”

He’s more reluctant than ever to call them. Recently, when his sister heard gunshots in the neighbourhood she asked him to call 911, but he refused.

“It’s an experience that unfortunately, you would have to be a person of colour to understand,” he says. “I don’t buy the police kneeling and hugging people, because we’ve been kneeling and hugging and praying for 60 years.”

He doesn’t feel that the case against Aaron Dean is being pursued properly. It troubles him that no-one from law enforcement has come to speak to him since the night of the shooting. It’s his belief that if he hadn’t spoken to the media the following morning, Atatiana’s death might not have been investigated.

He’s also upset with the pace of the trial.

“With the pandemic going on they said it could be 2021 before this thing starts. On the other hand, had it been a person or colour we’d be tried, convicted and have started our sentence already,” he says.

“We’re still holding our breath. Pardon the phrase, but we can’t breathe.”

There are about 1,000 “officer-involved shootings” in which someone is killed every year in the US. These statistics are not centrally collected but various organisations and researchers have been compiling the data, mostly from media reports.

According to one of these organisations, Mapping Police Violence, in 2019 black people represented 24% of those killed by police despite making up only 13% of the population.

Dr Philip Stinson of Bowling Green State University has also compiled an extensive database on police crime and, analysing cases where police have been arrested, has found that police crimes against black people tend to involve violence more often than police crimes against other races.

Image copyright

Reuters

Police officer Aaron Dean was booked at Tarrant County Jail two days after Atatiana Jefferson’s killing

Convictions for these crimes are rare. Between 2013 and 2019, Mapping Police Violence recorded more than 7,500 cases in which officers shot and killed someone, but according to Stinson’s database only 71 were charged with murder or manslaughter and only 23 were convicted of a crime related to the killing.

Since 2005, Stinson calculates, only five non-federal police officers have been convicted of murder.

When James Smith went on TV to talk about his neighbour’s death he learned that this was the seventh officer-involved shooting of 2019 in Fort Worth, a city of less than one million people.

But shootings are only part of the problem. In the midst of the George Floyd protests in early June, a Fort Worth police officer called Tiffany Bunton spoke out about the death of her uncle in police custody two years ago.

Image copyright

Getty Images

Christopher Lowe died in the back of a police vehicle after being detained by two officers. The body camera footage of his arrest shows officers dragging him to their car.

It’s disturbing to watch. Though he’s compliant throughout the arrest, the officers taunt Lowe as he struggles to stand up and to walk. He tells them he’s sick.

“I can’t breathe,” he says, “I’m dying.”

“Don’t pull that [expletive],” the officer says. And later, “If you spit on me bud I’m going to put your face in the [expletive] dirt.”

Thirteen minutes later Lowe was found dead of a drug overdose in the back of the car. Tiffany Bunton believes his death could have been prevented if the officers had called an ambulance, instead of ignoring his symptoms and insulting him when he told them he was unwell.

Five officers were fired in January 2019, as a result. A year later two of them got their jobs back.

When I asked James Smith if he was familiar with this case he simply replied, “That’s what we go through. So we avoid the police as best we can.”

Two weeks after Atatiana’s funeral, her father, Marquis Jefferson, died from a heart attack. His brother believes it was grief that killed him.

Her mother Yolanda Carr was in hospital the night her daughter was killed and was too sick to attend her funeral. In January she was well enough to return home, and James Smith said he’d treat her to lunch. He was waiting for the barbecue place to open when an ambulance screeched down the street and parked outside the house. He rushed over and found paramedics trying to resuscitate her.

She was wearing a T-shirt covered in portraits of her daughter, and lying on a cushion that Smith had given her, decorated with a print of Atatiana’s face.

Image copyright

James Smith

A blanket and cushion printed with pictures of Yolanda Carr and her daughter, Atatiana

In early June the mayor of Fort Worth, Betsy Price put out a statement on the death of George Floyd – who was killed in Minneapolis when officer Derek Chauvin knelt on his neck.

In the statement the mayor mentioned Floyd by name but referred to Atatiana only as Fort Worth’s “own tragedy”.

“She didn’t even mention Atatiana’s name,” Smith says. It felt like a knife being twisted in his gut.

As he watches protests all over the country in response to George Floyd’s death, he wonders why people didn’t respond to the killing of Atatiana in the same way.

“The quieter we are the more likely that Atatiana is forgotten and I don’t want her forgotten,” he says.

On 19 June Atatiana’s remaining family – her sisters and brothers – are launching a foundation in her honour, funded by donations they received in the wake of her death.

The Atatiana Project will focus on education and on improving relations between the police and the community. It will be based in the house where Atatiana was shot.

On Facebook, James Smith proudly posts pictures of a wall in his home, filled with framed photos of his children, nieces and nephews in their graduation gowns and mortarboard hats. They’re smiling, holding rolled up bachelors and masters’ degrees.

He and Yolanda Carr should be American success stories. A postal worker and a nurse who worked hard, saved money, educated their children and bought beautiful homes on a quiet street to enjoy into their old age.

But James Smith is not sure if he can be happy in this neighbourhood again.

“I look through my dining room window and I see Atatiana’s house. When I wash my dishes I look out of my window I see Atatiana’s house. When I sit on my back deck I see Atatiana’s house.”

And every time the image of that night comes back to him.

“I’m going to see these people coming across the street and going to the back of the house and bang! I’m going to see this when my great-grandchildren are born… when I’m sitting on a rocking chair.”

You may also be interested in:

Robert Jones was arrested in 1992, accused of killing a young British tourist in New Orleans. Four years later, he went on trial – by this time another man had already been convicted of the crime, but he was prosecuted anyway. The judge who sentenced the young father to life in prison now says his skin colour sealed his fate.

Locked up for 23 years – when the real killer had already been jailed (2015)

More Stories

Healing Streams Live Healing Services with Pastor Chris: Miracles Await this March 14th – 16th, 2025!

Essential Care for Hermann’s Tortoise: A Guide to Thriving Pets

Nail Decisions: Which is Better for You, Acrylic or Gel?