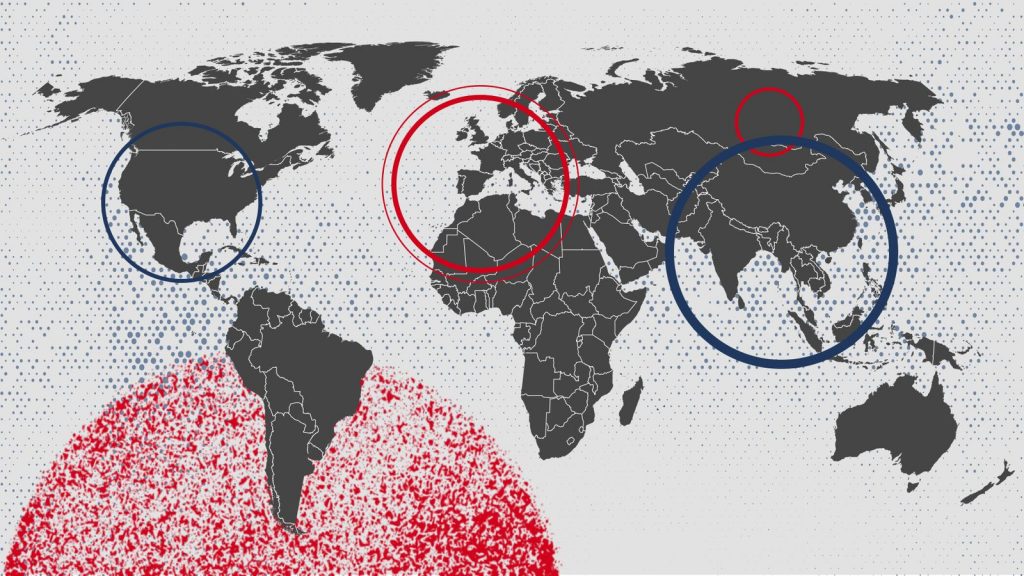

COVID-19 has infected millions around the world since emerging in China late last year, claiming the lives of more than 660,000 people and changing our way of life for some time to come.

Now, fears of a second wave of coronavirus are growing in many nations.

Here, Sky News’ foreign correspondents across Asia, the US, Europe, Russia and India reveal how the virus has changed these continents and countries – and what is likely to happen there in the coming months.

Tom Cheshire, Asia correspondent

China was ground zero for COVID-19 back in late 2019. Back then it was a mystery virus.

After confusion and cover ups, the government brought it under control just as it was becoming a global pandemic.

All that time, China and several other Asian countries and territories – notably Vietnam, Taiwan, Hong Kong and South Korea – weathered the pandemic well, avoiding the terrible death tolls of Europe and the US.

But second or even third waves have arrived and cases are rising again.

China has seen its highest daily total since April; Hong Kong has recorded more cases than it did in the original wave; a new outbreak in Vietnam has spread to six cities.

As depressing as that is, the virus is much better understood, as are the tactics for containing it – especially targeted lockdowns and aggressive quarantines – and governments have wasted no time in imposing those measures.

Hopefully that means Asian countries can avoid their health systems being overwhelmed.

But it also suggests that, for the whole world, there is a long, hard slog ahead. Success in containing coronavirus can only ever be temporary.

Greg Milam, US correspondent

The United States has less than 5% of the world’s population but almost a quarter of its coronavirus fatalities.

It has also been the stage for the world’s most public political and social argument over how to get the virus under control.

Even now, six months on, the president is still touting treatments disavowed by his medical experts.

It has been left to governors of the 50 states to stitch together a patchwork of responses.

It is widely accepted that the re-opening came too soon, even in states like California which locked down early and had some success, and the cost can be measured in daily record-breaking numbers.

Donald Trump says the case numbers are so high because the country has been so successful in testing – but the death count can’t lie and new peaks in California, Texas and Florida tell a grim story.

There are some early signs the number of new infections is flattening again, a little hope that Americans have got the message.

But doctors are warning of a death toll in the “multiple hundreds of thousands”. And leading scientists say the country needs a “reset” in its approach by October, or a winter catastrophe looms.

:: Listen to Divided States on Apple podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, and Spreaker

By Adam Parsons, Europe correspondent

The virus has had a profound effect on continental Europe in almost every way imaginable.

The death toll has been vast – in the four worst affected countries (Spain, Italy, France and Belgium), more than 100,000 have died so far.

Regions have been left traumatised – the north of Italy, Catalonia in Spain and the east of France, for instance, suffered terribly.

Economic losses have been huge with a continent-wide recession now looming.

There have been damaging political disputes that have stretched the European Union over borders, differing medical responses and, most bitterly, over how to fund a recovery plan.

The north and south have appeared polarised.

Germany, Europe’s biggest, richest nation, coped much better than its neighbours, perhaps due to long-term investment in its intensive care units and its proactive response.

Those countries that locked down faster often had the best outcomes, while Sweden bucked the trend and barely restrained its population – it has now had many more deaths than its Nordic neighbours.

Masks are mandatory in some places, but not in others. Social distancing rules remain commonplace.

Some Eastern European leaders have been accused of using the crisis as an excuse for eroding popular freedoms.

After a period of relative calm, the virus is re-emerging with significant outbreaks in Portugal, Spain, Bulgaria, Croatia and Belgium, among other places.

Few doubt that a second wave will hit Europe again.

The question is whether that will require a succession of tight rules focused on individual locations – or a return to the national lockdowns we saw earlier this year.

Diana Magnay, Moscow correspondent

The virus came late to Russia. That gave the authorities time to prepare – closing the borders in March, imposing quarantines on incoming travellers and massively ramping up hospital bed capacity.

But when it came, it hit hard.

There have now been 830,000 cases. Russia is still the fourth most infected country worldwide.

Although the case load is half what it was at the peak, it is still more than 5,000 new cases a day.

According to Russia’s president, the situation “remains difficult” and “could swing in any direction”.

Authorities credit the relatively low mortality rate of around 2.5% of cases to an effective and early response.

Certainly the Russian testing regime has been impressive, with 27.5 million tests carried out so far, though the picture in the regions is far from transparent.

Most Russians you speak to don’t trust the government numbers, but they are more than happy to be (mostly) done with quarantines.

Six weeks since lockdown was lifted in Moscow and face masks are ever more token.

The bars and clubs are packed. Worries about a second wave now an after-thought to the sweet taste of liberty and the hope that it lasts.

Neville Lazarus, India reporter and producer

India reported its first COVID-19 case six months ago on 30 January.

As the government announces the third phase of lifting its lockdown, the country recorded 52,249 cases in a day on Wednesday, breaching the 50,000 mark for the first time.

With more than 1.5 million cases, India is the third worst affected country in the world behind the US and Brazil.

Even though the Indian government is keen to project a low fatality rate of 2.23%, there have been 35,036 deaths reported so far.

The country is still in the first wave with no signs of the virus peaking yet, let alone flattening.

A major concern for the government is that large numbers of cases are showing up in smaller towns and villages in rural India.

The nation’s public health care system is utterly inadequate and in many cases non-existent.

The government spends just 1.2% of its GDP on public health and this has been going on for decades by successive governments.

The struggling public health care structure could collapse in the face of a severe pandemic affecting the poor.

India had one of the severest lockdowns for months and this had a detrimental effect on the economy.

Hundreds of millions of daily wage earners and contract workers were left with no earnings. They all migrated back to their villages and homes, inadvertently carrying the virus with them.

More Stories

Healing Streams Live Healing Services with Pastor Chris: Miracles Await this March 14th – 16th, 2025!

Essential Care for Hermann’s Tortoise: A Guide to Thriving Pets

Nail Decisions: Which is Better for You, Acrylic or Gel?