When I saw those figures, I got a big doubt. What, do our economic immigrants really earn better than the population of Quebec? And do they really earn more than their peers in Ontario?

Posted at 6:30 am

I’ve always been convinced the opposite, hence my surprise. Initially, in the context of the debate on immigration thresholds during the election campaign, I wanted to check where the gaps were.

Because let’s face it: strictly from an economic perspective, immigrants are more than welcome if they raise our collective standard of living, especially by earning better-than-average wages and paying more taxes to finance our services.

I checked the Statistics Canada data to be sure and the conclusions remain. However, with important nuances.

A first observation, then: so-called economic migrants, whom we welcome for their special skills, after the adjustment has passed, have better median incomes than the general population. The data is for the year 2019 – the most recent available – and is derived from federal income tax returns.

Thus, 10 years after their arrival, principal applicants for economic immigration had a median income of Quebec natives in 2019 of $51,400, or 38% higher than the general population ($37,130).

Not only do they earn more than Quebecers, they also earn more than economic immigrants from Ontario ($49,800) and British Columbia ($48,500), Statistics Canada data tells me.1. Wow!

Isn’t it surprising to learn that we often see the typical immigrant in Quebec as a taxi-driving math bachelor compared to a high-tech entrepreneur in Ontario?

In fact, immigrants selected for their skills are working more than the Quebec population because they are more educated (46% have a university degree, where the number of natives is double).

Wise people tell me that the comparison is biased because newcomers are younger than the general population, and retirees are often less well-paid. Very good.

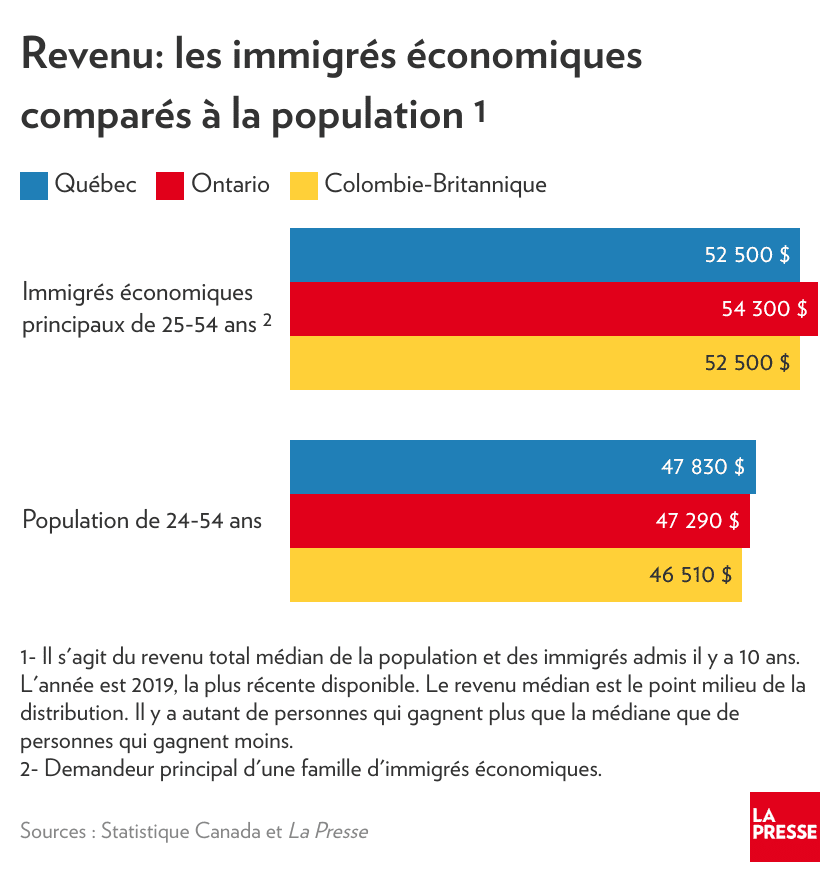

But here we target only 25-54 year olds to eliminate this compositional effect, even if the gap narrows, the advantage remains favorable to the main applicants for economic migration. Their median income in this age bracket rises to $52,500, a nearly 10% difference with the Quebec population of the same age.

They had the same median income ($52,500) as their counterparts in British Columbia and Ontario ($54,300), even 10 years after they arrived in the country. Alberta is in a class of its own ($65,700).

Quebec has a disadvantage: it takes longer for our economic migrants to reach and surpass the population median income than elsewhere in the country. Typically, catch-up here is five or six years after they arrive, while elsewhere, economic migrants earn roughly as much as others do upon arrival, according to the data.

Language problem? Recognition of diplomas? Perceptiveness of the host society? Or is Quebec’s low economic strength 10 years ago, when they arrived, a disadvantage reversed in recent years?

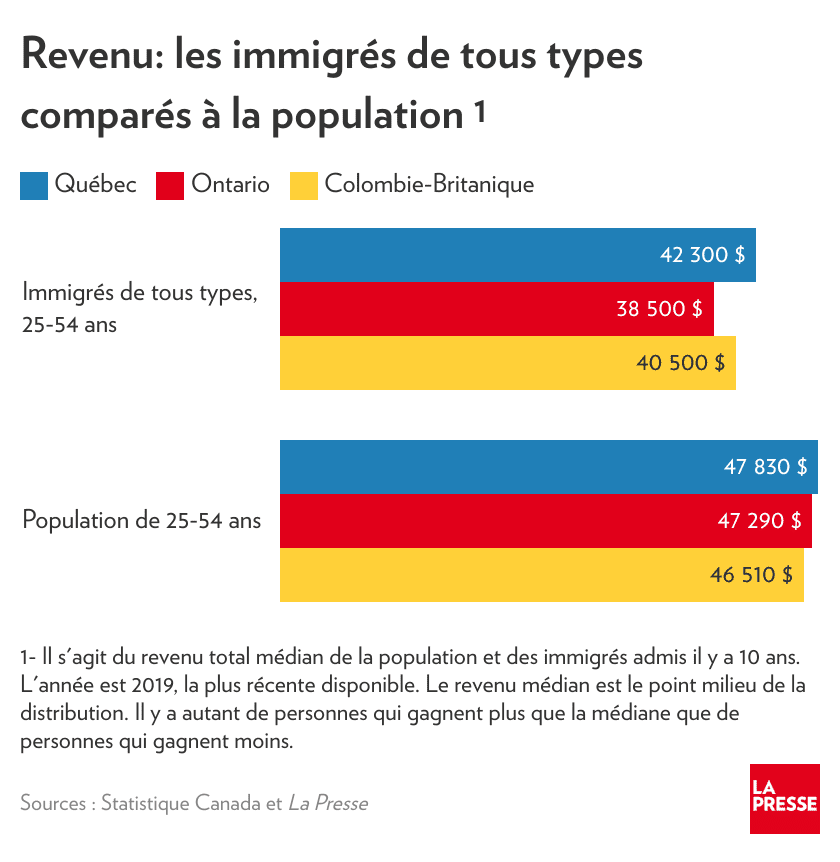

The picture changes when we include spouses and dependents of economic migrants as well as other migrants, including family-sponsored migrants and refugees.

All inclusive, and after 10 years, the median income of all immigrants aged 25-54 was $42,300 in Quebec in 2019, compared to $47,830 for the same age population, a negative gap of almost 12%.

Consolation: Disadvantages for immigrants are greater in Ontario and British Columbia than in Quebec.

The difference in Quebec’s favor comes from our immigration policy. Here, two-thirds of admitted immigrants are economic immigrants, according to a Statistics Canada database, compared with 50% in Ontario, which accepts more family reunification.

In short, our main economic migrants earn more than the same age population, but other types of migrants still occupy low-wage jobs.

In addition, the unemployment rate of immigrants remains slightly higher than that of natives, given their higher qualification rate for occupied positions (39% versus 26% of natives), even 10 years after entry. How is this possible with such a shortage of staff?

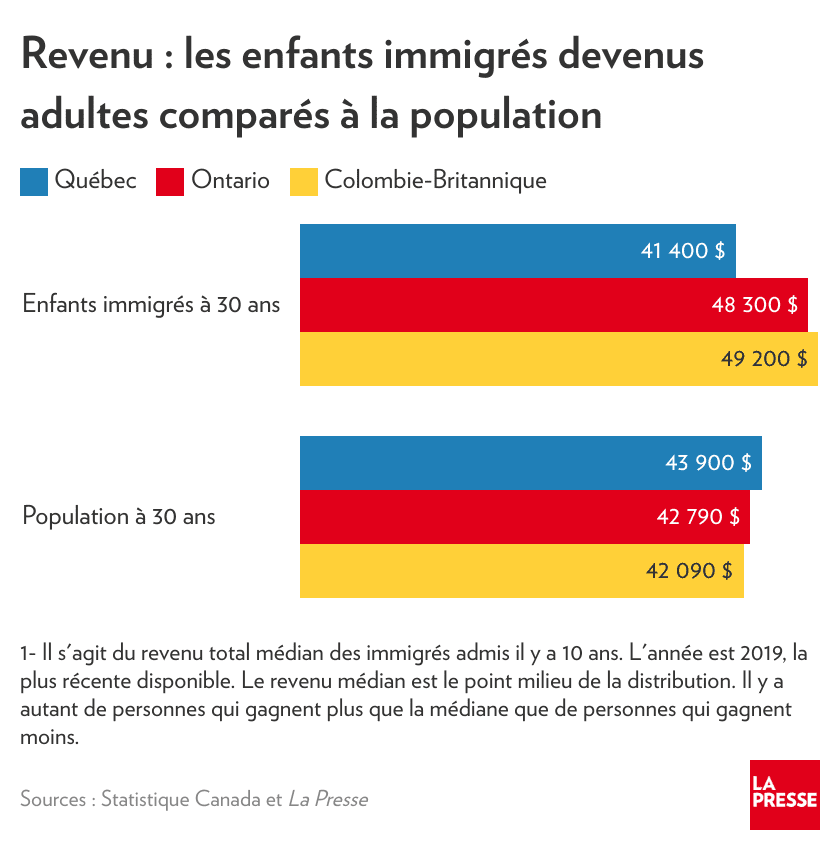

Another element must be taken into account in our assessment of immigrants’ contribution: the future of their children. Often arriving at a young age, these children study in the local education system and their career prospects improve greatly.

What’s more: According to data from Statistics Canada, children of immigrants, by age 30, earn significantly more than Canadians of the same age. The gap in their favor reached 13% in Ontario and 17% in British Columbia. The reason? Again, their greater propensity to study than Canadians born here.

In other words, economists are fooling themselves when they analyze only the immediate contribution of newcomers without considering the future of their children, 15 to 30 years later.

Unfortunately, Quebec stands out from the rest of Canada in this regard. Here, immigrants who arrived as children earn about 6% less, at age 30, than all Quebecers of the same age, even though they are more educated…

It is difficult to understand why. In the previous analysis, I came to two conclusions to explain the difference with other provinces. One: There is a clear gap between immigrant races in the propensity to study.

Two: Quebec offers a much lower salary for immigrants educated here than elsewhere in Canada. For example, a person of Haitian origin earns much less in Quebec than in Ontario, even though he has a similar propensity to study2. Here there is more discrimination, in short, the analysis needs to be taken further, especially, considering the field of study.

We hear a lot about the number of immigrants welcomed each year and their contribution in reducing or not reducing labor shortages. Migrants fill jobs, but also need health and education services as well as housing. This debate is not easy to resolve.

The angle of analysis I propose is that the contribution of immigrants to scarcity varies with income. It is a fact that many vacancies generally cause wages to rise, especially for immigrants, especially since certain positions are so scarce that it is possible to grasp its contours.

Of course, a better selection of immigrants helps things like better francization and integration, but according to my analysis, we need more openness in the workplace and a long-term vision of immigration.

1- Income includes everything, wages, salaries, own source income, investment income and government transfers. Only landed immigrants are counted, not temporary immigrants. Data taken from Immigrant Taxfilers Income Database (43-10-0027-01), updated December 2021. Data for the general population were compiled by Statistics Canada at their request Press. For the sake of brevity, the term “economic migrant” at the beginning of the text refers to the principal applicants and not their dependents.

2- The data is for the year 2017 and not 2019 (as in this column).