During the height of the lockdown, Manchester’s leaders and officials were braced.

With a population that includes some of the most impoverished neighbourhoods in the country, among the highest levels of underlying health conditions such as asthma, a large BAME community, lots of people in insecure, low-paid work and many areas of dense housing, the city was primed for the toll to be high.

Like everywhere, of course, there have been many lives lost, there are many grieving and many still suffering from the after-effects of contracting the disease during those months. Even so, Manchester did not go through a London-style outbreak early on and the figures suggest it fared comparatively well next to places with similar vulnerabilities.

Get the latest updates from across Greater Manchester direct to your inbox with the free MEN newsletter

You can sign up very simply by following the instructions here

The city’s mortality rate remains below the English average and well below the north west average.

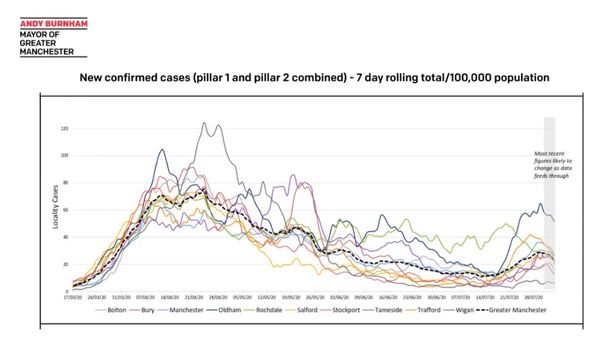

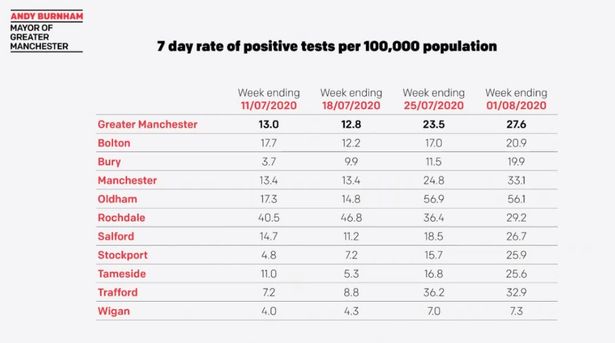

Until a fortnight ago, meanwhile, the rolling average for cases in the city since mid-March had been solidly mid-table for the ten boroughs, pretty much bang on the Greater Manchester average.

Its cumulative infection rate – in other words the number of cases recorded per 100,000 people since the start – stands at 621, around the average for the north west.

So by no means cheerful, but not what some had feared.

Some of that may have been down to the city deciding in the early days to test people on discharge from hospital before they were returned to their care home – despite government telling them not to – as well as a coordinated approach to infection control, more community testing than ministers had advised and a daily ring-around of nearly 100 care homes in the city at a time when PPE was short. Those in the town hall hope rates in the city may have been dampened by strategy at least as much as luck.

But times have moved on and the virus’s journey has changed.

In the third week in July, Manchester’s infection rates began to climb rapidly, taking it to second place out of Greater Manchester’s ten boroughs, doubling in a fortnight, at one point overtaking Rochdale and nudging it into the zone where ministers start to pay attention.

(Image: PA)

While still low, its positivity rate – the percentage of tests that come back showing people have Covid – has also been inching up, a pattern insiders note is not good news, as they would like to see the increased testing of recent weeks come back with a growing percentage of negatives.

Rather than tearing through care homes and hospitals, the coronavirus is now circulating within the community as a whole, dispersed into all corners of the city.

During the week of July 19, there were 80 cases recorded in the whole of the city, according to data published by Public Health England, across roughly ten neighbourhoods. (PHE doesn’t map cases where there’s fewer than two in an area.)

The following week that had nearly risen to 139, spread across at least 17 neighbourhoods.

Last night’s data, for the week to August 2, maps out 185 cases across at least 30 neighbourhoods, with no obvious pattern. It’s now getting easier to count the places that haven’t recorded infections in the last seven days than those that haven’t.

They are spread right across the city: from Heaton Park in the north, to Merseybank in the south, Piccadilly and Ardwick in the centre and Abbey Hey in the east. There were 16 cases in Moss Side West in those seven days – the highest, followed by 11 in Crumpsall South.

Of all the major trends officials think are going on, there is a takeaway headline: people under 40. As elsewhere in Greater Manchester, hospital admissions and deaths remain low, an indicator that this is now less of an issue among older people. That includes care homes, where stricter testing and infection control is currently seeing 6pc of establishments reporting cases this week, compared to well over 50pc at the peak.

Instead, there is a fear that a whole section of younger people have simply tuned out.

Whether that’s groups of people mixing in homes, or drinkers not bothering with social distancing – and bars themselves in many cases not imposing safety measures – or staff having to work in pubs without sufficient protection, it is among this age bracket that the virus is now multiplying.

“Younger people is the big thing,” says one worried senior figure. “The people who have just looked at the news and thought ‘oh, it’s older people’.

“But that’s what’s dangerous. If it’s high now among the under 40s, does it start spreading among older people as we get into the autumn?”

While Manchester is currently subject to stricter lockdown rules – as is the whole of Greater Manchester – due to rising infection rates, council insiders believe this may yet be a warning to other cities of trends to come.

“I think it’s a story the country will have to grapple with as to how high you can let the infection rates among under-40s get before people get really poorly.”

The message from government in the past week has undoubtedly been confused. As one man stood outside a shop in Manchester this afternoon was overheard saying to his friends: “I played football with 12 people on Monday night, a contact sport.

“But I can’t go and sit in my sister’s garden. How does that make sense?”

In the absence of clear and logical messaging from Westminster, local leaders are trying to clarify the approach into two strands, both in the city and outlying boroughs.

Manchester council leader Sir Richard Leese said this week that the advice as a whole is simple. Stripping out the caveats, you can’t currently have social visitors.

Given that realistically Greater Manchester Police are not going to knock on front doors and ask who is in your house and why, the second strand relates to enforcement around businesses.

Bars in Manchester, as anyone who has been for a drink in recent weeks knows, are hugely varied in their approach to safety measures. Many are taking no contact details at all, providing no sanitiser and effectively carrying on as usual. Others are Fort Covid: your temperature taken, number recorded and hands cleansed before you’re allowed to sit down.

(Image: Joel Goodman)

This inconsistency was on the radar of leaders even before the new restrictions were announced last week.

Minutes from Greater Manchester’s emergency Covid meeting of July 29 show there were concerns areas here would need to go further than the government was indicating.

“The main issue around track and trace in licensed premises does need to be addressed and GM should consider doing more that the national guidance around enforcement or encouragement to do better,” they agreed.

“Further discussions will be held at the Senior Gold Command to agree a more targeted multiagency approach. Some license premises chains are taking the approach more seriously than others, with a suggestion that messaging be sent to major breweries across GM.”

This weekend, we can expect that message to be stepped up. On Wednesday Sir Richard referred to ‘high profile’ and ‘visible’ enforcement measures being on their way.

Aside from the age profile, there is also a continued risk among BAME communities.

The neighbourhood map shows the virus spread across all sorts of demographics and ethnicities, but nonetheless Manchester has been trying to use newly-acquired data on exact communities affected to target their messages.

There have recently been higher rates among North African and Portuguese African communities, for example. (The national track and trace system simply sent these cases through as ‘African’, however, a vague term that meant little to those on the ground. Local track and trace investigations were needed both in Manchester and Salford to distinguish that in fact there were two quite distinct groups affected, separately.)

Equally, ahead of – and during – Eid, the council was talking in detail to Muslim community leaders about safety messaging. Immediately after last weekend, sources both in Manchester and elsewhere said that seemed to have worked well. But, as elsewhere, there remains a concern about multi-generational and sometimes overcrowded households, particularly in the south Asian community.

Either way, the city is now concentrating on stepping up clear advice to everyone in Manchester over the summer, ahead of the days really drawing in.

(Image: Manchester council)

Leaders here don’t want to see the economy closed down and they certainly don’t want to see the public health graphs running in the wrong direction.

“The wide geographical spread of new confirmed cases is evidence that the rate of community transmission is increasing – this means more people are contracting the virus in their local neighbourhood and in people’s homes,” says the city’s public health director, David Regan.

“So it remains crucially important that people continue to follow the public health safety measures designed to keep us safe.

“Targeted engagement work has already begun in local areas where transmission rates are rising to remind people that we all still have a role to play to limit the spread of the virus – particularly amongst young people where infection rates are growing.

“For example, in parts of north Manchester the numbers have gone up marginally, so socially-distanced, outdoor engagement events will take place over the weekend explaining the new restrictions and what they mean.”

He notes that the numbers have not sky-rocketed but climbed, now at an average of 24 cases a day across the city, compared to 17 a day over the previous month. So the numbers in the local neighbourhoods are still relatively small, but they want to stop them from rising further.

Local outbreaks have been expected, meanwhile, so the city’s own local track and trace system has been responding where there has been a cluster of cases in an office or a restaurant, court, bar or similar venue.

Data from last week shows local infection control departments have been dealing with a rise in those as well as broader community infections. The graph for cases dealt with by localised track and trace system across Greater Manchester has climbed steadily since mid-June, which you might expect.

But Manchester itself has dealt with the biggest single weekly number of such cases so far, tackling 20 in the week to July 27.

That included two workplace outbreaks, one in the city centre and one in north east Manchester, where the infection was said to have been spread among staff rather than customers.

So the virus is permeating all areas of life. As the city’s public health department tries to keep a lid on it, the messages bear repeating.

“We are all used to the mantras – wash our hands, keep our distance, don’t visit other people’s homes – but these simple things remain essential in our fight to slow the pandemic,” adds David Regan.

“And it’s important if you do have symptoms, stay at home and book a test.”

The latest statistics – which haven’t yet been completed by Public Health England – suggest Manchester’s rate may just now be flattening out, or even starting to fall.

Officials will be obsessing over spreadsheets in the coming days for evidence of whether the new measures are working.

But the patterns spotted by leaders here so far could yet prove a lesson for others, not least those sitting in Whitehall.

More Stories

Healing Streams Live Healing Services with Pastor Chris: Miracles Await this March 14th – 16th, 2025!

Essential Care for Hermann’s Tortoise: A Guide to Thriving Pets

Nail Decisions: Which is Better for You, Acrylic or Gel?