In November 1938, when Ruth Adler Schnee was 15 years old, Nazi soldiers smashed the windows of her family’s home in Dusseldorf, Germany. They snatched the door from its hinges, smashed Limoges porcelain and threw Biedermeier furniture out the window, as part of a violent campaign targeting Jewish families in the Holocaust prologue.

Adler Schnee’s parents had a relationship with art and literature – his father, Joseph, ran an ancient bookstore while his mother Marie, had studied at the iconic Bauhaus design school – and among the items destroyed was the Nazi-owned Paul Signac watercolor. stabbed into small pieces. The Adlers were not at home at that time, and when they returned everything was destroyed. They collected pieces of Signac’s paintings and then returned them, even though they were never the same.

Adler Schnee’s living room design for Rosenthal Residence, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, 1961

Early difficulties

As a teenager, he risked being jailed for sneaking up to the famous 1937 Munich Degenerate Art Exhibition, organized by the Nazi party to show what they considered the decay of that era. Wearing a large brown fur hat as a disguise, Adler Schnee was immediately transported by the colors of brilliant artists such as Oskar Kokoschka, George Grosz and Wassily Kandinsky.

Adler Schnee’s vibrant polyester textile, “Fission Chips,” 2012. Credit: PD Rearick

Already, Adlers experienced tightening restrictions on Jewish life. No longer able to enter Christian shops, families rely on their caregivers to leave groceries at their doorstep at night. In the winter of 1939, Joseph was sent to the Dachau concentration camp. He was released, miraculously, after Marie’s relentless petition, and returned to his family starving, without shoes and losing his front teeth. Within a few days the family began preparations to flee to the United States. Other extended family members will die in Lodz and Auschwitz.

“Is someone being recognized again as a human being? Oh, that is too beautiful to be true,” wrote Adler Schnee, a teenager in his diary as he crossed the border into France. When Adlers finally arrived in Detroit, where Joseph was promised work that never materialized, Marie sewed mattresses in a factory while the family made lampshades at night.

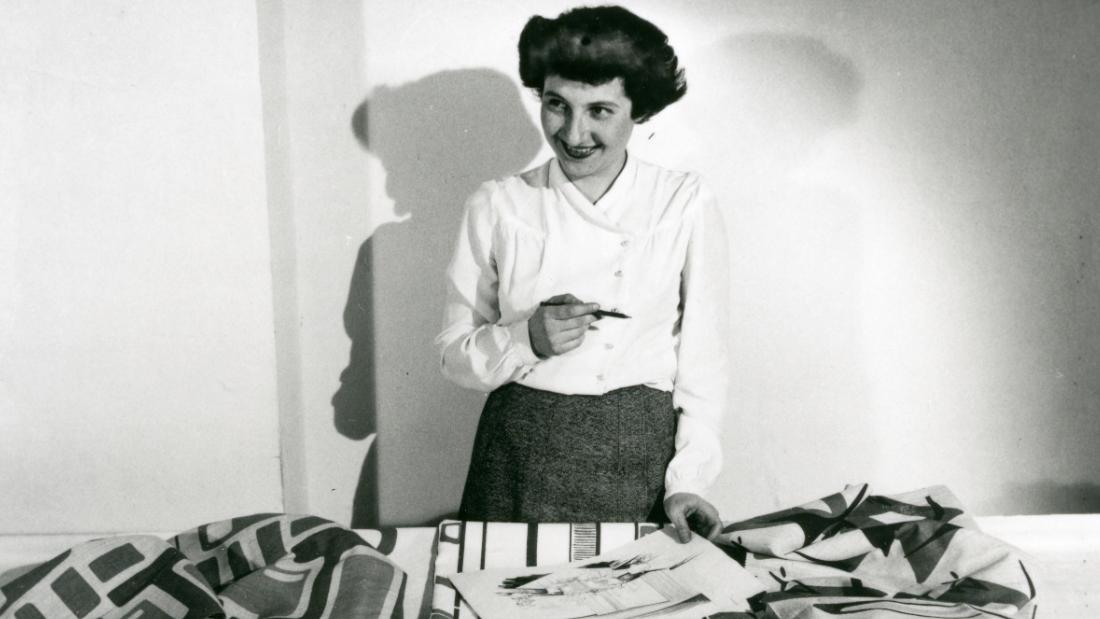

Ruth Adler Schnee works with designs for Slits and Slats and Pits and Pods.

Modernist vision

Adler Schnee turned his attention to textiles in 1947 while looking for curtains for the prize-winning interior he designed for a contest sponsored by The Chicago Tribune. He could only find antiseptic floral motifs that seemed to come from an outdated past. Influenced by liquids, the biomorphic forms of Alexander Calder, Henry Moore and Isamu Noguchi, he began to make his own cloth with bold abstract patterns. It is elevated in bright colors and minimal, organic form. “A design doesn’t just have to talk, it has to sing,” he said.

Adler Schnee Textile “Wireworks,” 1950, in which he used ink on white dream batteries. Credit: PD Rearick

In the same year, he founded his own textile studio and met Eddie Schnee, a Yale graduate who had studied economics and became enamored with himself and his fabric. She became her husband, her business partner and her most passionate cheerleader. (Adler Schnee remembers during the 2013 talks at Cranbrook that Eddie liked to say, “Ruth is my hobby,” when asked about her entertainment).

The pair opened a colorful studio and a joint home appliance store in 1949. When Adler Schnee continued to design fabrics and interior spaces, Adler-Schnee Associates brought to the Midwestern market the best of modernist design: Chinese white Rosenthal, enamel Copco, enamel Marico, Marimekko fashion and folk art from Mexico and South America. Finally moving to the first floor of a department store in downtown Detroit, their business became the epicenter in the city for cutting-edge design. When most businesses, especially after the riots of the 60s, were emptying the city, Adler-Schnee captivated the crowds with creative marketing.

The Schnees are not content to only sell the work of leading designers, but also try to educate the public about the beauty and practical elegance of everyday objects. Visiting a shop must be indoctrinated in modernist ethics, its simple and simple form.

“Can’t a cooking spoon have a beautiful shape?” Adler Schnee asked, remembering in the oral history of the Smithsonian manuscript for one of the store’s radio points. “Broom brooms can be bright, cheerful and comfortable in the hand.” Their vision was not always convincing: the Eames storage unit, after failing to sell, was finally sequestered from the showroom to store toilet paper.

Adler Schnee’s “Construction” textiles, 1950, were made with ink on bleached linen. Credit: PD Rearick

Adler Schee finally believes that a good design must combine patterns, colors and textures in functionality. “If that has been achieved, it will never go out of style,” he told Dwell in 2018.

It was a rubric that he applied to his own works, from lyrical textiles to the smooth interior arrangement. Despite experiencing one of the most horrific periods of the 20th century, his works always exude brightness, love for color and shape, and material excitement. He found beauty in his circumstances: a singing design.

More Stories

3 Top-Rated Laptop Power Banks in 2024

Essential Care for Hermann’s Tortoise: A Guide to Thriving Pets

Nail Decisions: Which is Better for You, Acrylic or Gel?